(This is about writing, not religion -- unless your religion is your writing.)

In the New Testament, we often see Jesus calling the Scribes and Pharisees, and hypocrits in general, to repentance. Among their sins, He names the tendency to focus too much on the letter of the law and not enough on the spirit thereof.

In particular, He chastises them for making it harder for others to get into the kingdom of heaven. (See Luke 11, starting around verse 39, but especially 52; also Matthew 23, especially verses 13 and 15.)

But I don't recall much recorded in which He chastised people for bad grammar or bad word choice or unfashionable language style.

In LDS scripture, we see a note that Adam had a perfect language.

No, wait. It says, "pure and undefiled".

Now, that fact was important for us, but the language itself seems not to have been as important. We don't have his language, so we can only speculate as to its nature, particularly, in what way it was pure and undefiled.

Does that mean he used perfect grammar? Or does it mean something else?

Where did the grammar rules for any language currently in use come from? Who wrote our dictionaries and our manuals of style?

We might suspect it, but linguists will tell us it is true. The grammar, dictionaries, Thesaurses, style manuals, all of the tools we have for analyzing what we have written come from our own hands. The language itself predates them.

And?

I am not arguing that skill with language is bad. It helps to be able to be precise when we speak or write. Precision is not evil, unless it is used for evil.

And I admit it, by the way. I am not nearly as precise in my Japanese as I am in my English. Up until

just a few days ago, I have been unwilling to attempt to write fiction in Japanese.

I will try to help fellow writers with grammar, word choice, style, structure, and other tools of technique. But I often feel at conflict with myself in the attempt.

Here's why.

Even though linguists call the rules things like "rules of production", those rules are not used in producing speech or rhetoric. They are used in producing analyzable strings of the sorts of symbols that linguists use to analyze.

The best use of grammars and dictionaries is as aids in understanding what we've written.

And manuals of style are artifacts of fashion. They are in constant flux.

If you need a technical report, sure. Use that manual of style. Lots of other reports-kinds of writing work best when they follow some manual of style.

When writing fiction for a closed genre, there are manuals of style. (But they still exist in a state of flux.)

But.

Closed means closed. Here's another hint from linguists. Meaning is not found in reproducing what has been done before as much as it is found when creating something new.

That means that your style as a writer exists in the tension between your efforts to follow the rules and your occasions to break them.

I have tried to help several authors whose grammar and word choice are less than standard. I think of four specific cases where my help seems not to have helped.

I myself was waylaid by a structure Pharisee in a writers group where I participated briefly last year --

My

first novel did not need a hook in the first chapter. It was not intended to be a bestseller. An ordinary sort of hook will get in the way of that story. Yet, I let that (well-intentioned, I think) more experienced writer induce me to get a lot of practice writing myself in circles, trying to get that hook into place.

Practice is practice, and is not completely useless, but I needed to be working on other things by now, and that novel is not yet finished. The delay is in no small part caused by my spending too much time focusing on the wrong things. I was trying to put a hook in when I needed to be

fixing the metastructure.

And this is where several of my friends are now stuck. They are focused on hooks, grammar, word choice, style, flow, and other such things when they need to be focusing on other things. Or, perhaps, taking a break and reading, or writing something else, or getting out into the real world, so they can come back and look with fresh eyes.

Some of them need to do what I ultimately did -- throw several months of edits in the junk pile and go back to a previous version from before they started listening to the wrong advice. One, in particular, may need to throw multiple months of edits in that junk pile and just publish the novel.

With its warts.

And I'm not actually convinced that my efforts on my first novel to avoid misleading people by my references to the Church I belong to are completely necessary. I may still be doing too much re-write instead of just clearing a bunch of unnecessary linkage from my first novel, where it sits in one of my blogs.

With its warts and non-standard features and love handles and such.

I was raised on books that didn't make the best-seller list. I don't remember some of their names. The grammar was wrong in many, although it tended to be consistent.

I say, wrong. I should say, non-standard, because there is no wrong grammar without context, and a novel is its own context.

So, what am I saying?

Writers, do not fear Microsoft's grammar checker.

Turn off the spelling checker, too. Only run the spelling checker once a day or so, and don't believe everything it tells you.

Keep the mechanical grammar checker turned off.

Emphasize that. You do not want your grammar sounding like it was written by a cookie-cutter.

Are you in a panic? Settle down. Microsoft is a company that claims to sell 80-20 solutions. Even if those claims were accurate, that's twenty percent wrong. But it's more like 20-80 and a lot of bluster. These guys are salescrew. What they sell is confidence.

You know, the Music Man, but with no heart.

What you need is confidence, not grammar checkers. Sure, your first novel may not be the best. You can polish it a bit, but there comes a point where you improve more by leaving it behind and writing the next one.

Why? Because the next one allows you to build new skills, and some of those are the skills you need to get that first one polished right.

(Don't be afraid to come back in six months or six decades and see what you can do with the ones you left behind. Arthur C. Clarke did that with

Against the Fall of Night and produced

The City and the Stars. I personally prefer the former, but both are good SF novels, and he thought the latter told the story better according to his older self's point of view.)

So you don't have the confidence? What instead?

If you can find a group of readers (beta readers is a well-used term right now, critique group is another) who can help you in useful ways without encouraging you to chase your tail, such a group can be useful. If they don't help you with the confidence after a little while, thank them and find new people to help.

Prayer helps, if you know God. If you don't know God or don't believe, meditation and listening to your heart is another way to describe it.

It's not wrong to learn the rules, but you must write new stuff to learn the rules better than you know them now. (This rant is too long, or I'd explain that. But it's another mathematical principle.)

The reason you write is to communicate something meaningful to people. Rules can only help about twenty percent of the way. The rest is the work you put into getting the message into the media.

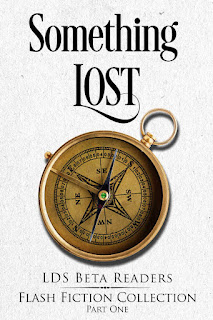

This one is a little different from the previous books. It's a small anthology of short-short

pieces in a format called "Flash Fiction", where we write a complete

story in 1000 words or less. It has an introduction, some sort of plot

element, and a resolution.

This one is a little different from the previous books. It's a small anthology of short-short

pieces in a format called "Flash Fiction", where we write a complete

story in 1000 words or less. It has an introduction, some sort of plot

element, and a resolution.